HOTC #5: LSB 358, From Heaven Above to Earth I Come

A couple of weeks ago, we covered what I referred to as “THE great Lutheran Advent hymn.” Today we move with the seasons, and consider what I would safely consider THE great Lutheran Christmas hymn - Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich Her, or “From Heaven Above to Earth I Come.”

The Angel Gabriel Appearing to the Shepherds, by Alfred Morgan, 1876

The Author

“contrafact

noun

con·tra·fact ˈkän‧trəˌfakt

variants or contrafactum

pluralcontrafacts -ts or contrafacta -tə

: a 16th century musical setting of the mass or a chorale or hymn produced by replacing the text of a secular song with religious poetry”

Vom Himmel hoch is said to have sprung from Luther’s pen in late 1534, as a Christmas hymn fit for his family and acquaintances at Christmas festivities that year, and possibly as a sort of “theme” to a Christmas pageant for his children. It was originally a contrafactum, that is a sacred text set to a secular tune. In Luther’s case this was the tune “Ich kumm aus frembden Landen her,” or “I come from foreign lands,” a popular tune of the time. Luther’s text, 15 verses of four lines each, was set to this original tune when published in the “First Wittenberg Hymnal” the next year. Indeed, the resemblance of Luther’s text to the text of the original secular song is striking, and his composition was certainly inspired by it:

“I come here from foreign lands

and bring much news to you.

I bring so much of the news to you,

more than I will tell you here.”

“From Heaven above I come here;

I bring you good news.

I bring so much good news to you,

of which I will sing and tell.”

In its original form, it was Luther’s only contrafactum, and is one of just three Christmas hymns penned by the great reformer.

The hymn was republished in 1539, this time with a new melody, almost certainly by Luther himself. It is reasonable to assume, from both the composition of a new tune for this hymn and from the fact that the previous version had been his only contrafactum, that the great theologian had some serious second thoughts about the use of secular music in a sacred setting, once this hymn had made it into hymnals and (presumably) from there into church services. More on that later, though.

The Text

The text is essentially a lengthy meditation on the middle section of Chapter 2 of St. Luke’s gospel, the famous Nativity story. The “Luther family Christmas pageant” origin story of this hymn makes much more sense when the overarching structure of the text is examined:

The first five verses are in the first person, but it is not, as the title might at first suggest, Christ speaking - it is, rather, the angel appearing to the shepherds outside Bethlehem. This would’ve been the part taken by an older child, or perhaps a student, as it takes up a full 1/3 of the entire text. The first verse is introductory, letting us know who the angel is and what the subject of the pageant is to be. The remaining verses of this “solo” part are a rumination on the words of Luke 2:11-12.

The sixth verse is a sort of “chorus,” where the entire cast, or indeed perhaps the entire family, would’ve joined in. It separates the angel’s section (the first five verses) from the series of “solos” and “choruses” that follow.

The remaining verses are a series of solos (obvious by their singular pronouns) and choruses (again, the pronouns) in which those involved in the Luther family pageant sing of the nature of the Child in the manager, and of the longing of mankind for the grace and salvation that He brings. Luther’s command of the New Testament is on full display in the second half of this hymn, as themes from St. Paul’s epistles in particular weave in and out of the text.

The final verse is another chorus, as Luther winds up by echoing the Gloria, which is by happy coincidence the following verse in St. Luke’s gospel.

The entire translation appearing in Lutheran Service Book is the work of Catherine Winkworth, with editorial changes by the editors of both the present hymnal and Lutheran Book of Worship.

The Tune

The tune we know for this hymn is, as noted above, the second tune given for this text, and is almost certainly Luther’s own work. Exactly why Luther changed tunes for the 1539 re-publishing is unknown, but the anecdote (often ascribed to the tune O WELT, ICH MUSS DICH LASSEN, also by Luther) that he “was embarrassed to hear the tune of his Christmas hymn sung in inns and dance halls.” seems likely to be applicable in this case as well. I refer the reader to Paul Nettl’s fantastic Luther and Music for further sources on the subject.

Now, I’m not going to get too far into this subject, because it’s a big subject and there will be a better time for a bigger discussion on this, but one of the justifications often given by those who wish to - I’m being delicate here - make changes in the proper way of doing things is but “But even LUTHER used secular bar tunes to make his hymns!” Clearly, the evidence here, albeit circumstantial, is that the one time Luther did so (this hymn), he quickly had misgivings about it (assuming, by the way, that he had even authorized the printing of the original version, which is disputed) and wrote something more ecclesiastical and liturgical. If we break down Luther’s 37 (!) chorales, 15 of them are original compositions by Luther. Of the other 22, thirteen of them are paraphrases, shortenings, or some other dervation from Latin chants. Four were German religious folk songs. One, and only one, of the chorales (this one) ever had a secular folk song for a tune, and Luther rectified that as quickly as publishing would allow.

So no, Luther’s chorales do not justify your praise band. Indeed, isn’t it absurd to argue that the chorales justify a system that belittles those same chorales?

Hey, it’s my blog, I’ll go there if I want to. Anyway, back to this awesome tune.

VOM HIMMEL HOCH shares many similarities with Luther’s more widely-known EIN FESTE BURG IST UNSER GOTT, a fact that I realized even on my drive home from church today, wherein I caught myself humming EIN FESTE BURG even though I had left church with VOM HIMMEL HOCH in my mind. It’s easy to do: like EIN FESTE BURG, VOM HIMMEL HOCH plunges the full length of a major scale in its course, and the two share a nearly identical final phrase (depending on whether or not you use the passing tone to prepare the final cadence).

There’s a ton of momentum going on in the contours of this hymntune, and it’s important for the organist to exercise some control: if the hymn moves too fast, the gravity of phrases and the structure of the text (pointed out earlier) are lost in the desperation of the singers to spit out the words quickly enough. Fast tempi are always a temptation when dealing with lengthy hymns, and at 15 (!) verses, no one is arguing that From Heavin Above isn’t lengthy. Indeed, it was split into two hymns (and the twelfth verse removed) in Lutheran Worship. It’s also infinitely playable (probably the easiest chorale to get one’s fingers around in the entirety of Lutheran Service Book), which can further contribute to a fast tempo. But it’s worth remembering that the folks who came to church are there exactly for this kind of thing, and there’s no reason to rush or exaggerate for the sake of a few seconds or a couple of minutes. Indeed, rough math says that this hymn, taken at 60 beats per second, should last right at 8 1/2 minutes. Increasing the tempo to 80 beats per minute gets the hymn over with in just less than 6 1/2 minutes, and doubling it (!) to 120 beats per minute gets the hymn through in (obviously) about 4 minutes, 15 seconds. But what’s 2-4 minutes, if the congregation is left unable to recall or meditate on any of the words or any of Luther’s premises because they’re trying to spit out the words as fast as they can?

You won’t get a warning from me about playing too quickly very often (more organists drag than speed, in my experience), but this is one of those times.

That said, this is definitely not a hymn that can be allowed to drag, either. The only section of the shepherds’ encounter with the angel in Luke 2 that Luther omits is “Fear not…” There is no fear in these words, only joy, and it must be played (and sung) joyously.

Christmas is a holiday that was very much central to Lutherans in Early Modern Europe (as it is for many today), and Christmas has, to some extent, always been a very Germanic festival in its traditions and celebration. It comes as no surprise then, that Vom Himmel hoch and Luther’s tune for it caught on quickly and became one of the most popular German-language Christmas hymns.

This is evidenced by the sheer quantity of compositions involving the text, the tune, or (usually) both. There are so many, in fact, that I’ve chosen to make a bulleted list here, and these are just some of the highlights:

Organ compositions

Johann Bernhard Bach (second cousin and near-contemporary of the more-famous Bach)

Samuel Michael David Gattermann

J.S. Bach (12 [!] settings for organ)

BWV Anh. 63, a short, simple hymn introduction in the key of D major

BWV Anh. 65, a bicinium, very reminiscent of BWV 711, in C major

BWV 769, the “Canonic Variations on Vom Himmel hoch,” which are honestly too mind-boggling to go into here. These five variations represent Bach at the very height of his complex contrapuntal powers, setting the tune between parts of a canon, or indeed in canon with itself. This video over on the fantastic gerubach YouTube channel gives you some idea the depth of the genius involved in Bach at this level, and the way he harnessed complex contrapuntal forms to convey theological concepts and to paint scriptural events muscially. Aboslutely astounding stuff.

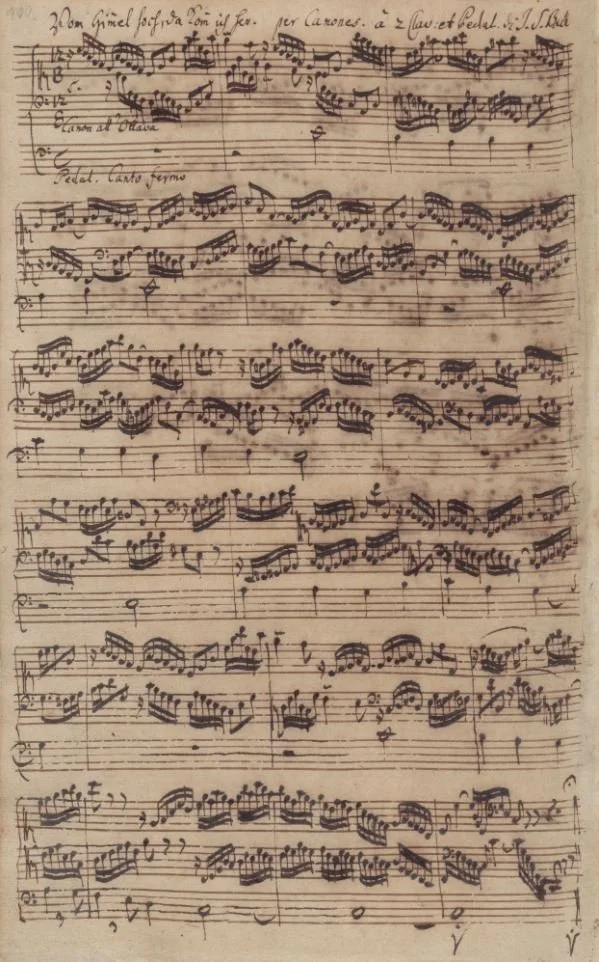

The first page of Bach’s manuscript for the Canonic Variations on Vom Himmel hoch, BWV 769

Again, this list is not exhaustive, but offers a few highlights (seriously, go watch the BWV 769 video!).

Choral compositions

Late Renaissance and early Baroque choral settings appear from:

Michael Praetorius (at least three settings, one each for 2- 3- and 5-voice choir)

Samuel Scheidt (SSWV 299, for sopranos in two parts with continuo)

Johann Hermann Schein (for three voices and continuo)

Johann Christoph Bach

six verses of the hymn are set in his cantata Merk auf, mein Herz und sieh dorthin

J.S. Bach

the first stanza of the hymn appears in his 1723 version of his Magnificat, BWV 243

the tune appears three times in the Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248

part of the hymn is set in his Christmas Oratorio

his cantata Vom Himmel hoch

the melody appears in incidental music that Mendelssohn composed for Jean-Baptiste Racine’s play Athalie

Igor Stravinsky

Chorale Variations on Vom Himmel hoch, for choir and orchestra, an arrangement of the Bach canonic variations, with extra contrapuntal lines added by Stravinsky

Again, this is necessarily a limited list, as I’ve come to the conclusion that once one goes looking for settings of this tune, one can find as many as they’d like if they have the time. Likewise, the recommendations made available below are necessarily limited. Have I missed on of your favorites? Let me know.

Settings of this hymn and/or tune can be found in:

For organ:

Oxford Service Music for Organ: Manuals only, Book 1

Concordia Hymn Prelude Library, Vol. 11

30 Kleine Choral Vorspiele, Op. 135 (Reger)

Chorale Preludes and Postludes for Manuals, Vol. 4

Pachelbel Complete Organ Works, Vol. 2

Bach Complete Organ Works (pub. Barenreiter), Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, and 10